EACH year on May 16, Teacher’s Day is marked by heartfelt celebrations—flowers, cards, and touching tributes to honour educators. But for me, it’s not just about those in schools or lecture halls.

It’s also about someone once called “Cikgu” (Teacher), though he never stood at a blackboard or wore formal attire. That someone was my father—a former Malay Regiment soldier with a dream of becoming a teacher.

I remember it clearly: during a trip back to our hometown, my father and I were at the market when a neatly dressed man, about his age, greeted him warmly. “Cikgu Ali! Lama tak jumpa… apa khabar?” They hugged and laughed like old friends. I stood by, confused—my father was never a teacher. He had worked as a soldier, then as a driver and transporter of plantation workers.

On the way home, I asked, “Abah, kenapa kawan abah panggil abah ‘Cikgu’?” He was quiet for a moment. Then, staring out the window, he began to tell a story that changed how I understood what it means to teach.

Growing up in a poor village in Teluk Intan during the pre-independence years, my father had few resources but a deep love for learning. His friends often came over after school, and he would patiently guide them through lessons. They began calling him “Cikgu”—not for any title he held, but for the way he taught with sincerity.

He once dreamed of studying at Sultan Idris Teachers’ Training College (SITC) in Tanjung Malim—a prestigious institution that produced many Malay educators and thinkers. He passed Standard Six and was offered a place. But as the only surviving son among seven siblings, financial hardship forced him to choose duty over dreams. He joined the army to support his family.

Yet, the name “Cikgu” stayed with him. His friends never forgot the one who helped them when they were close to giving up. One of them— the man at the market—did go on to SITC and became a headmaster. But he still called my father his first teacher. I was deeply moved by his story. Suddenly, I understood why my father was so insistent about education. Though he never stepped into a teacher training college, he instilled in us the values of a true educator—discipline, sincerity, and a love for knowledge.

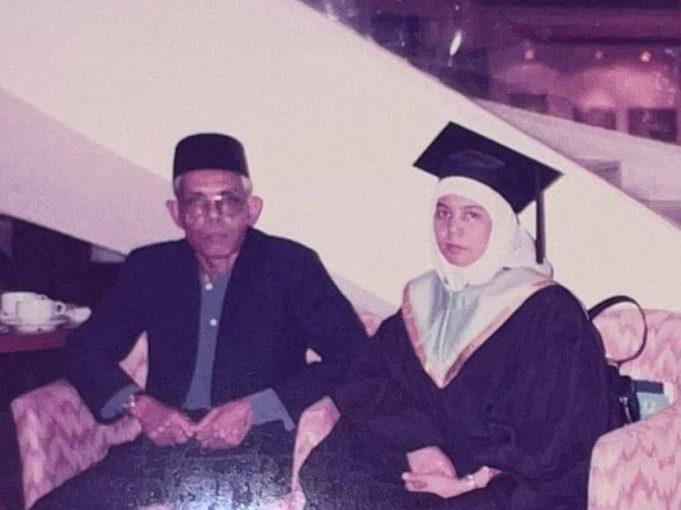

Five of his eight children went to university. Three decades ago, when I became a lecturer, even though I wasn’t a schoolteacher, he was proud. I once found an old school essay of mine that he had kept, in which I wrote: “Being a lecturer suits a woman. I can also give my services to the public through education.”

It’s been ten years since he passed. But every time I pass through Tanjung Malim, I think of him—of his unrealised dream and the legacy he left behind. To me, Teacher’s Day isn’t only for those in classrooms. It’s for anyone who brings light to others’ lives, with or without a title.

I’m reminded of a saying of Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him): “The best of people are those who are most beneficial to others” (Hadith reported by al-Tabarani in al-Mu‘jam al-Awsat). My father may never have held a certificate or faced a class, but he taught through kindness, sacrifice, and wisdom. That, to me, is the essence of being an educator.

Happy Teacher’s Day to all who teach, guide, and uplift—especially those like my father, Cikgu Ali, remembered not for titles, but for the lives they touched. May Allah grant him a place in paradise among the righteous.

Sr Dr. Zuraini Md Ali is an Associate Professor at the Department of Building Surveying, Faculty of Built Environment, University of Malaya.