The following article is submitted to the Editorial of Malaysia Gazette by reader, Hafiz Hassan.

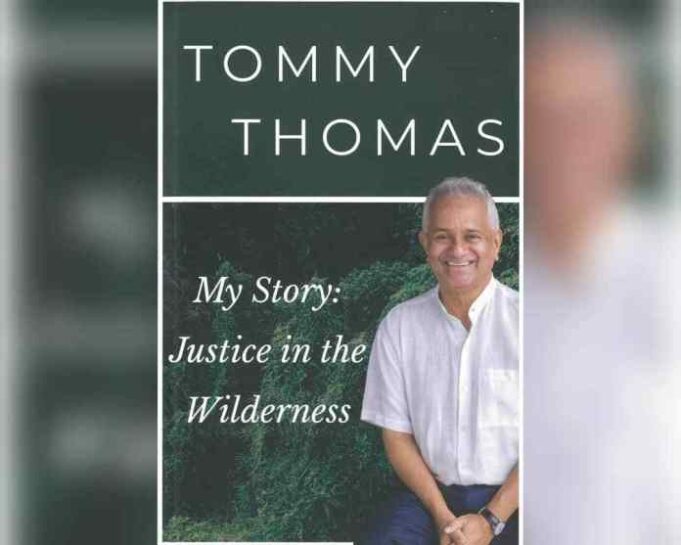

The published memoirs of former Attorney General (AG), Tommy Thomas, have received strong reactions – even condemnation. A police report has been lodged for criminal defamation and he is now under police investigation.

Could the publication be prevented or stopped by an interim injunction?

In the English case of A-G v Jonathan Cape Ltd; A-G v Times Newspapers Ltd [1976], the facts were straight forward. C was a cabinet minister from 1964 until 1970. Throughout that period C kept diaries which contained details of discussions held in cabinet and in cabinet committees and disclosed the differences between cabinet ministers on particular issues. The diaries also contained details of communications made between C and senior civil servants together with criticisms of certain civil servants. The diaries were kept with the express intention of publication at some future date.

The fact that C was keeping such a diary intended for publication was known to C’s colleagues in the cabinet. C died in 1974. After C’s death a firm of book publishers proposed to publish C’s diaries in a series of volumes entitled ‘The Diaries of a Cabinet Minister’. At that time the existing cabinet contained a number of individuals who had been C’s cabinet colleagues between 1964 and 1970. A newspaper, acting with the consent of C’s literary executors, published serialised extracts from what the book publishers intended to be the first volume of C’s diaries.

The Attorney General (AG) brought two actions (i) against the book publishers and C’s literary executors and (ii) against the newspaper, seeking permanent injunctions restraining them from publishing the diaries or extracts therefrom.

In support of his claim the AG contended that all cabinet papers and discussions and proceedings were prima facie confidential and that the court should restrain any disclosure thereof if the public interest in concealment outweighed the public interest in the right to free publication.

The basis of that contention was that the confidential character of those materials derived from the convention of joint cabinet responsibility whereby any policy decision reached by the cabinet had to be supported thereafter by all members of the cabinet whether they approved of it or not, unless they felt compelled to resign; and that accordingly cabinet proceedings could not be referred to outside the cabinet in such a way as to disclose the attitude of individuals in the argument which had preceded the decision, thereby inhibiting free and open discussion in the cabinet in the future.

The AG also contended that advice tendered to ministers by civil servants and personal observations made by ministers regarding their capacity and suitability were also confidential and could equally be restrained by the court.

The Queen’s Bench Division – equivalent to the High Court in Malaysia – dismissed the AG’s actions, but only on the facts of the case. According to the court, the first volume of C’s diaries dealt with events 10 years previously and disclosed no details of discussions which should remain confidential. As such, since there was no ground in law which required the advice given by senior civil servants and ministerial observations on their capacities to remain confidential, there were no grounds for restraining publication of that volume.

The court, though, delivered a strong pronouncement of the principles tending to such publications, namely:

(i) the equitable doctrine that a person should not profit from the wrongful publication of information received in confidence was not confined to commercial or domestic secrets but extended also to public secrets. It followed that where a cabinet minister received information in confidence the improper publication of such information could be restrained by the court when it was necessary to do so in the public interest;

(ii) the doctrine of joint responsibility was an established feature of the British form of government and therefore matters leading to a cabinet decision were to be regarded as confidential. The maintenance of that doctrine within the cabinet was in the public interest and the application of that doctrine might be prejudiced by the premature disclosure of the way in which individual ministers had voted in the cabinet on particular issues;

(iii) the courts had power to restrain the publication of cabinet material when it could be shown (a) that such publication would be a breach of confidence; (b) that publication would be against the public interest in that it would prejudice the maintenance of the doctrine of collective cabinet responsibility; and (c) that there was no other facet of the public interest in conflict with and more compelling than that relied on.

So, an ex parte interim prohibitory injunction could have sought from the court to restrain the publisher and the author from publishing the memoirs and extracts therefrom.

As far back as 1988, one of the country’s great legal minds, Edgar Joseph Jr said, “There is plentiful authority supporting such a course of action.” (see Cheng Hang Guan v Perumahan Farlim (Penang) Sdn Bhd).

The court will be the best forum to decide whether the balance of convenience lies in favour of granting an interim prohibitory injunction in the interest of justice.

-Hafiz Hassan-

Editorial note: The views expressed are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of Malaysia Gazette.