The following article is submitted to the editorial of MalaysiaGazette by reader, Hema Letchamanan, School of Education, Taylor’s University

The pandemic has magnified many inequities within the society, including in education. In 2017, the data from UNESCO Institute for Statistics [1] reported 617 million children and adolescents worldwide are not achieving minimum proficiency levels in reading and mathematics. More recently, the World Bank (2019) has estimated that about half of the children in low and lower-middle income countries cannot read a simple paragraph at age 10.

Learning poverty is based on the notion that every child should be in school and be able to read an age-appropriate text by age 10.

Proficiency in reading is especially important as it contributes to the overall performance and achievement in school. Past studies have also shown that children who are not reading at grade-level are more likely to drop out of school, and this is even more so for children experiencing poverty (Hernandez, 2012) as low proficiency in reading means children are unable to use their reading skills to excel in other subjects.

In a study by UNICEF on urban child poverty in Kuala Lumpur in 2018 found that 51% of children who are five and six years old are not attending preschool and 13% of children who is at the end of their lower secondary school age are not proficient in reading[2]. Due to COVID-19, it is predicted that an additional 10 percent of children globally will fall into learning poverty (UNICEF, 2021).

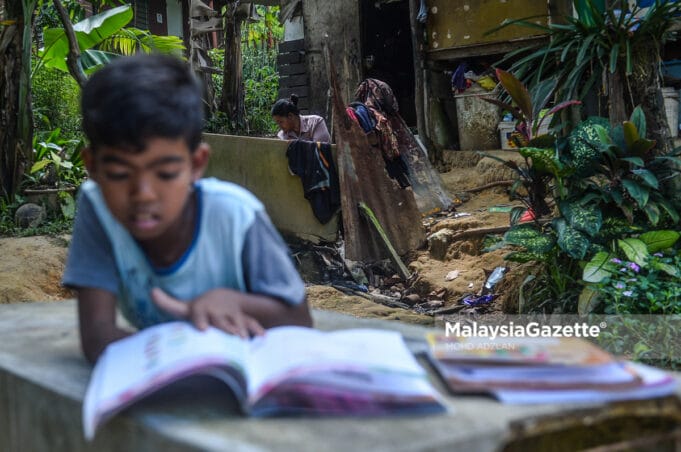

With worldwide education system being disrupted, it reinforces the societal divide among students especially those who are from vulnerable communities as they faced two main issues – lack of digital infrastructure, and home environments that are not conducive to learning.

Finger on the pulse: Challenges of Online Learning in Malaysia during the Pandemic

While some students were able to continue device-based learning from the comfort of their homes, the story was different for students from lower income households. This can be seen clearly in some states such as Pahang, Kelantan, Sabah, and Sarawak.

Sabah education director, Dr Mistirine Radin said about 52% of the students in the state did not have access to the Internet or smartphones, computers or mobile gadgets that are needed to participate[3] in online learning. Sarawak State Education Minister Datuk Seri Michael Manyin Jawong in June said over 50 percent of students in Sarawak had no Internet access or electronic devices to follow online learning at home during the MCO phase[4].

Even in Klang Valley, many students are struggling to continue their learning because of the lack of conducive home environment to support online learning and suitable resources to study at home along with limited accessibility to the internet. A survey by the Ministry of Education (MOE) on Teaching and Learning (PnP) online involving 670,000 parents with a total of 900,000 pupils found only six per cent of pupils had personal computers, tablets (5.67 percent), laptops (nine percent) and smartphones (46 percent)[5].

Addressing the Online Learning Challenges Which Increases the Learning Gap

While some students are fortunate to have their own space, devices, connectivity and other facilities, several students in Malaysia continue to lack the same. Many live-in close proximities and large families and as such the creation of learning spaces for the students could motivate them to perform better.

For example, one of the initiatives undertaken by Taylor’s University’s education and architecture students was to create a comfortable space for children from underserved communities to study called The Nest Project. The Nest was designed with sustainable materials and simple designs with learning nooks that allowed the students to concentrate and feel motivated to study. Till date, 22 Nests have been created for underprivileged families at PPR Lembah Subang 2 and Flat Taman Seri Berembang, Port Klang that have helped children to have a conducive and comfortable place to study.

Moving forward: Filling gaps in education with an empathetic approach

Understandably, the shift from offline to online learning has overwhelmed the school system but these issues, especially the issue of literacy among students, have always been there and the pandemic has further exacerbated these issues. But it doesn’t have to be that way. Educators, schools, and the civil society can join hands to lend a more empathetic approach to education, one where the student remains the focal point.

We as a community can work together to bridge the learning gap. Recently, the School of Education at Taylor’s University began a reading project called Projek BacaBaca – a community initiative that aims to improve the reading proficiency of students experiencing poverty to ensure that they do not fall behind in their studies and inculcate the love and joy of reading among the children.

From one-to-one reading lessons twice a week with reading coaches, to mentorship sessions, community initiatives like this not also encourages more young people to volunteer and participate in social causes to build back better. All one needs is a telephone connection.

Efforts like these are a step forward in eliminating learning poverty in Malaysia. Reading is a gateway for learning as the child progresses through school. The inability to read slams the learning gate shut for the students as they will face hardship in learning other areas such as math, science, and humanities.

The pandemic has forced the most vulnerable students into the least desirable learning situations as they face various challenges to receive the quality education they deserve. We need to address these challenges today to build a better future for the youth of tomorrow.

Hema Letchamanan,

School of Education,

Taylor’s University

Read More:

6 siblings fight for chance to use 2 gadgets during PdPR

PdPR : It’s tough! Slow internet, difficult to focus